Podcast Episode 8 - 1995 (Flaming Lips)

A masterpiece of mostly whimsical psychedelia, Clouds Taste Metallic is my favorite Lips album and the final showcase for Ronald Jones, whose kaleidoscopic lead work echoes Hendrix and Kevin Shields (My Bloody Valentine), even as it explores new sonic territory. This album and about 100 shows were his final statement before leaving not just the band in mid-’96, but the public eye altogether. Clouds also marked the end of the “Drozd as Drummer” era, by which I mean he continued to play drums on recordings, but his role in the band changed from full-time drummer to electronica-obsessed multi-instrumentalist as the Flaming Lips embraced Dream Pop. Not that Clouds wasn’t pop. It was. It’s just that the melodies were wrapped in explosions of firepower.

Transcription

Theme Song: Mike Nicolai, “Trying To Get It Right” [Bandcamp]

Welcome to Don't Call It Nothing, the podcast dedicated to the lost history of '90s roots, rap, and rock 'n' roll. I’m your host Lance Davis and today we’re going to visit Oklahoma City in 1995.

Before we do that, though, lemme acknowledge this past week of music losses. It’s like, “I get it, Death. You’re all powerful. How about taking a few weeks off, rest up, maybe get ready for the college football season?” Anyway, the death parade started last week with Tom T Hall, one of my favorite country songwriters. If you’re unfamiliar with him, go to Spotify, and check out the compilation, Storyteller, Poet, Philosopher. That title sums up Tom T. And if “Mama Bake A Pie” don’t choke you up, you’re a bad person. The next day we lost Don Everly, the older of the Everly Brothers, who remain one my favorite country AND rock ‘n’ roll acts. And finally, the passing a few days ago of Charlie Watts, the only Stone worth liking [laughs]. He was one of rock 'n' roll’s greatest drummers and he did it without creating a persona, keeping up with trends, or projecting any fake tits bullshit. In that sense, he was both anti-Jagger and anti-Richards. He was just a bloke who enjoyed hanging out with his kids, grandkids, and dogs, a classy, dapper, one-man repudiation of the culture that surrounded him. For that I'll be forever grateful. Godspeed, Charlie.

The needle in the needle’s disguise

Amidst this litany of obituaries, it was also quietly announced about a week ago now that Michael Ivins, the Flaming Lips’ bassist since 1980 -freakin-3 (!), has left the band. Wayne Coyne’s statement on Instagram was very positive, betrayed no animosity, and even hinted that this was in the works for awhile. That said, even if you leave a job on good terms, it’s been 38 dadgum years – shout out Bobby Bowden. There’s gonna be a lot of complicated emotions to process for Ivins, Coyne, AND longtime drummer, keyboardist, and symphonic genius Steven Drozd. I get it, though. Being in a touring band is stressful under the best of circumstances. Being in a touring band during a pandemic – or trying to be a touring band, more accurately – that has to be on another level of suck. To be fair, Ivins did this for a long while, so I’m hoping he’s retiring because he can afford to retire. Young bands aren’t so lucky.

For example, when The Flaming Lips released Transmissions From The Satellite Heart in the summer of 1993, it basically went nowhere. Given that their first album for Warner Brothers, the previous year’s Hit To Death In The Future Head, also went nowhere, you couldn’t blame the band if they felt like they were spinning their wheels on the major label treadmill. I think the biggest problem with Hit To Death is that it had a few good songs, but wasn’t really a strong album. That drummer Nathan Roberts and guitarist Jonathan Donahue , who you might know from Mercury Rev and to which he returned, they bailed on the Lips even before that record came out. Bad sign. But, Transmissions is damn near flawless. In my opinion, the dumbest thing Warners did to the Lips was right after the album was released they went out on a brief tour opening for Porno For Pyros and then immediately after that went out on a long tour opening for the Butthole Surfers and Stone Temple Pilots. Brilliant strategy! One of the best bands of the decade gives you one of their best albums ever and you have them playing to empty fucking seats. But don’t worry, your drummer is hanging out with Gibby Haynes and Scott Weiland and definitely not doing drugs.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the poor house.

On March 5, 1994, Beavis & Butthead – then at the apex of their popularity – mildly praised the video for “She Don’t Use Jelly” and the song slowly started to gain traction. And then Lollapalooza came calling, so for 24 dates in July and August of 1994, the Lips headlined the second stage. Between the novelty success of “Jelly” and the fact that these badass songs were finally being played in front of, you know, actual human beings, Transmissions started moving units. So much so, in fact, that the Flaming Lips opened 1995 by appearing on The Jon Stewart Show. On the January 11th episode, the Lips played both “Jelly” and “Mountain Side,” one of the better tracks on their 1990 artistic breakthrough – and the album that got me into the band – In A Priest Driven Ambulance.

Speaking of which, two weeks after the Stewart appearance, on January 28, the Flaming Lips played Priest in its entirety. Now, this wasn’t something bands did in the ‘90s. Having a band play an album front to back was something you saw a lot of in the 2000s and 2010s, especially on the festival circuit. This was not that. The Lips were playing a small club in Norman called The Water Palace and luckily for us, someone was smart enough to record. Keep in mind that Coyne's voice is a little wobbly and the tape's kinda fucked up [laughs], but it’s still worth listening to because you get Drozd on sledgehammer drums and the great Ronald Jones on slide guitar. Here’s an excerpt.

That’s the Flaming Lips from the Water Palace in Norman, Oklahoma, with “Five Stop Mother Superior Rain,” on some days my favorite Lips song. And I may be wrong, but I think this is the only time “Five Stop” was ever performed. The original recording featured Roberts on drums and Donahue on guitar, who actually were more than capable sidemen. They do well on Priest. Hit To Death, it might not be their fault that those songs don’t work. I have no complaints about their work on Priest. That’s a masterful album. That said, going from those guys to Drozd and Jones was like adding Grant Hart and Nels Cline to the Lips. It’s impossible to overstate what a luxury it was for Coyne to have Drozd, this powerhouse fucking drummer who could also play – lemme see here – oh yeah, EVERYTHING. And then to ALSO have Ron Jones on free range space guitar? That’s an embarrassment of riches.

So, listen to this. “Stand In Line” is a perfect example of how the change in personnel elevated even the mundane. The original recording of “Stand In Line” is one of the lesser tracks on Priest. Not terrible, just so-so. However, when filtered through Jones, the track becomes something special. Check out this excerpt.

What in the fucking world??? [laughs] What are these sounds??? Ronald, tell us what these sounds are! THAT’S the power Jones was bringing to the table as the band started recording Clouds Taste Metallic in the spring of ’95.

“Spin: Do you consider Clouds to be the end of an era?

Wayne: I think Steven and I would say it is now. That that was the peak of when we thought of ourselves as a rock band – loud guitars.”

A masterpiece of mostly whimsical psychedelia, Clouds is my favorite Lips album and the final showcase for Jones, whose kaleidoscopic lead work echoes Hendrix and Kevin Shields (My Bloody Valentine), even as it explores new sonic territory. This album and about 100 shows were his final statement before leaving not just the band in mid-’96, but the public eye altogether. Ronald Jones effectively disappeared after his stint in the band. Clouds also marked the end of the “Drozd as Drummer” era, by which I mean he continued to play drums on recordings, but his role in the band changed from full-time drummer to electronica-obsessed multi-instrumentalist as the Flaming Lips embraced Dream Pop. Not that Clouds wasn’t pop. It was. It’s just that the melodies were wrapped in explosions of firepower.

That’s The Flaming Lips at the late, great Maxwell's in Hoboken, New Jersey, on December 11, 1995. As with Clouds Taste Metallic, "The Abandoned Hospital Ship" opened the show with Drozd playing a small keyboard set u right next to his drum kit and Coyne on vocals just breaking hearts. Halfway through, the song erupts into spasms of violence as Drozd pounds his kit and Jones folds the space-time continuum to take us through a wormhole. The album version is similar, but opens with the hum of a film projector as Coyne sings over the mournful piano. The apocalyptic feel actually anticipates The Soft Bulletin. At :24, Jones enters in the left channel, his spidery lead playing a single-string countermelody. At 1:14 we hear a mellotron positioned center-left as well as Coyne's ghost vocal, followed by Jones introducing the guitar riff that takes us to the song's second half. At 1:59, Drozd comes in on drums with Bonham-esque heavyocity. Listen to that fucking snare! Ivins then drops in on bass, wiggling around the main melody, as Jones summons ball lightning. "Hospital" eventually gives us bells, more sound effects, more guitars, and finally a theremin. It’s the big, old, black golden buzz of Apex Lips.

For all of the hotshot firepower on display, though, the unsung hero of Clouds Taste Metallic is Michael Ivins, who is endlessly creative, playful, and intuitive. Listen to him on "Psychiatric Explorations Of The Fetus With Needles" and "Bad Days." It's pure bippity bop carnival bass. Or, check out "Placebo Headwound." He's like McCartney on Sgt Pepper's, the pulse of the rhythm section, walking up and down the fretboard suggesting the melody, but never playing it directly. "When You Smile" and "They Punctured My Yolk" also echo late '60s McCartney. I highly recommend listening to this album all the way through and JUST listening to Ivins. You will not be disappointed. He wasn’t just “the bass player.” He was an integral part of these arrangements and the Lips would not have been the same band without him.

Oh, my Jesus, it's worse than you think

Here’s the thing, though. It’s hard for me to separate Clouds Taste Metallic from its context. The album came out in September, but in May, during a break from recording, the Lips did a brief west coast jaunt, which is where I caught up with them. They played a pair of shows at Moe’s, one of Seattle’s best venues at the time, and they also played an in-store at Cellophane Square in the U District. This was May 6, 1995. Seventeen days earlier the various members of the Flaming Lips were at home when this happened.

How does a massive fucking terrorist attack two miles from your house not impact your art, life, and headspace? That this was domestic terrorism, homegrown cracker ass motherfuckery, made it a million times worse. 168 dead, 19 of them children, hundreds injured, tens of thousands with PTSD, depression, anxiety, and various other perfectly understandable psychological reactions to the bombing. And I would include the extended family of the Flaming Lips in this latter group. Coyne himself admitted as much that day at Cellophane Square.

Fast forward to 13:16 to hear Wayne Coyne’s story about the bombing, followed by “You Must Be Joking”

Let’s consider the Oklahoma City bombing from Ronald Jones’ perspective. His dad is black, his mom is Filipino, and he was born in Hawaii where that combo of ethnic influences would barely register. Dad then moves to Oklahoma, home of the 1921 Tulsa Honky Riot, where people who looked like Ronald weren’t just attacked and killed by white mobs, they were literally bombed by fucking airplanes and then blamed for their own massacre.

So, fast forward to April 1995 and as the news leaks out that the perpetrators aren’t Middle Easterners seen speeding away from the downtown area, which was reported in the immediate wake of the bombing. In fact, the terrorists were these same weak, insecure white dudes like McVeigh who are always blaming government and minorities for their own mediocrity. The difference is that instead of just talking talking forever talking, a certain subset of Caucasian male feels emboldened to build bombs and then set off these bombs so as to inflict massive casualties on innocent people. The terror is the point. The cruelty is the point. And if you’re a hyper-sensitive artsy type who’s half-black and half-Filipino living a few miles from a bomb site where people were deliberately murdered by a white supremacist, how are you supposed to respond to that? How do you compartmentalize that? Or do you? And what if maybe there was an undiagnosed psychological disorder or condition already floating around in there?

When you combine all of these factors it’s not surprising that Jones hated “Evil Will Prevail,” the penultimate track on Clouds. He wasn’t complaining about the music. Who’s not gonna love Coyne’s voice and acoustic guitar up front and center in the mix, with what sounds like a clean electric guitar in the left channel and a mellotron in the right channel harmonizing on the song’s melody, not to mention the third act rock band eruption? I mean, he’s not dumb. No, Ronald objected to a song in which the bad guys win.

Knowing evil will prevail

Knowing that evil will always win...

Those are the final words of the song. Artistically, I get it. Coyne was also trying to process this horrific event and he’s not wrong. Evil prevails sometimes and he lives two miles away from the evidence. But, I also see Jones’ side of this. It’s easy for a comfortable white dude like Wayne to make lemons out of lemonade. Ron’s lemons look like strange fruit. The stakes for him are way, way higher. And while I wouldn’t say he quit the band because of the bombing, I bet it’s why he quit show business. Think about it. If you’re Jones, already hyper-sensitive and psychologically fragile, how do you know one of these cracker dumbfucks doesn’t wanna make an example of the half-black half-Filipino guy on stage? Fuck that.

Still, it’s always critical to recontextualize. And in this case, it’s important to remember that within the context of the record, Coyne doesn’t actually let evil win. Yes, he may have allowed it to briefly prevail, but the final song on Clouds ends on a hopeful, optimistic note.

That’s the Flaming Lips at The Fillmore in San Francisco, on May 12, 1995, about a week after I saw them at Moe’s. And sure, Coyne doesn’t quite hit the high notes, but taken in context, the band trying to muster up any note of optimism following such a horrific event has to mean something more than just the next song on the setlist. The fact that it’s a song about hating your job is besides the point. This is how art works. Sometimes events overtake intent. Artistically speaking, I almost couldn’t blame the Lips had they decided to release Clouds with “Evil” as the last song. Given the events of April 19, 1995, it was not inaccurate. But, that ain’t who Wayne Coyne is. He embraces spectacle, schtick, and artifice with every damn bit of his soul, like a psych-pop Willy Wonka. Walking around in a bubble suit, releasing songs on a USB drive that are buried inside of a life-sized gummy skull (true story), playing with a bubble machine, playing with a smoke machine, having a giant set Christmas lights twinkling behind the band on stage, and conducting parking lot experiments where dozens of people play boom boxes at the same time. Coyne’s whole goddamn raison d’etre is to be a light in a world with so much darkness.

For years, I dismissed the gimmicks and wished Coyne got back to songwriting, but I think I get it now. When you live two miles from a terrorist bomb site and you come to terms with the fact that you live amongst a lunatic fringe of violent extremists and thousands, if not millions, of people who may not do the actual dirty work of the extremists, but you know that if Jim Crow were reinstituted tomorrow, they’d be all, “Oh gosh. I wish there was something I could do. My hands are tied. I mean, not literally like yours, but metaphorically, which is way worse!”

In the face of such darkness maybe the best thing Coyne did was worry less about songwriting in the traditional rock sense and instead began to curate fun, psychedelic shows designed to make people happy, where it’s less about the songs and more about the experience. And yes, I realize that sounds fucking trite and maybe I’m normalizing a different kind of mediocrity. But, I don’t know. Is it? I think there are far worse outcomes than introducing colors of the rainbow so pretty in the sky onto the faces of people going by.

That’s the Flaming Lips from January 28, 1995, at The Water Palace in Norman, Oklahoma, the night they covered In A Priest Driven Ambulance in its entirety. Wayne hits most of the notes, but the best part is it explodes into a kaleidoscopic hailstorm, goes back into the ballad, and then finishes with more hailstorm.

That’s gonna conclude our deep dive into the 1995 Flaming Lips. You don’t have to hate your boss at your job to subscribe to this podcast, but it might help. Please go visit the Don’t Call It Nothing Facebook page and website. Dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com. Like, comment, become a member, tell yo mama, and tell a friend.

Talk to ya next time when we explore the wonderful world of 1996 alt.country!

Remembering Tom T Hall: Joe Henry, Iris DeMent & Joel R. L. Phelps

With the recent passing of legendary country songwriter Tom T Hall, I want to showcase three different mid-’90s covers that demonstrate how Hall’s influence transcended not just mainstream country, but his own ‘60s/’70s heyday: Joe Henry - I Flew Over My House Last Night, Iris DeMent - I Miss A Lot Of Trains, Joel R. L. Phelps - Spokane Motel Blues.

"30,000 feet below me you were fast asleep

And 30,000 feet above I almost stopped to weep

I wonder did you toss and turn as I roared out of sight?

I flew over our house last night"

With the recent passing of legendary country songwriter Tom T Hall, I want to showcase three different mid-’90s covers that demonstrate how Hall’s influence transcended not just mainstream country, but his own ‘60s/’70s heyday. In fact, it was the release of 1995's 2-CD set, Storyteller, Poet, Philosopher that first pointed me the way toward Tom T’s back catalog. It’s way out of print and pricey, but available on Spotify, so check it out. The first cover is "I Flew Over Our House Last Night" and it comes from Joe Henry’s 1993 LP, Kindness Of The World. Henry sings as Gary Louris adds lots of Clarence White-esque steel bends on lead guitar. Add Marc Perlman (bass), Razz Russell (violin), Paul Kelly (piano), Bill Dillon (pedal steel), and Mark LaFalce (drums) and this is perfect slow burn country heartbreak.

In a career of great Iris DeMent vocals, this track from Real: The Tom T Hall Project is right near the top. I'm not sure when it was recorded, but it sounds like her band circa 1996's The Way I Should (The Troublemakers). Solid guitar twang and pedal steel, but Iris' bluesy vocal phrasing is the revelation.

Real: The Tom T Hall Project is one of my favorite tribute comps. When it came out in 1998, several tracks were a regular part of the country radio show John Ratliff and I did at the University of Alabama ("The Lost Highway"). Johnny Cash, Iris DeMent, Kelly Willis, and Calexico all deliver gems. But, I think the most unexpected performance is Joel R. L. Phelps, then starting with The Downer Trio, but only a few years removed from Silkworm. He gets inside the raw emotions of "Spokane Motel Blues" in a way that no one else on this comp matches. It's a miracle of a performance, a perfect snowglobe of longing and despair.

I know they're dancing in New Orleans

And old Chicago's bright as day

I'm stuck in Spokane in a motel room

And I wish I had a Dolly Parton tape

Podcast Episode 7 - 1994 (The Blues)

If you love the blues, treat it with respect. It’s not about making white lawyers comfortable with their appropriation. It’s about acknowledging that this primordial American music was enriched by the best white blues musicians simultaneously as it was colonized by white people displacing the root black audience. It’s ok to interrogate this part of the genre’s evolution.

Transcription

Theme Song: Mike Nicolai, “Trying To Get It Right” [Bandcamp]

All right, welcome to Don't Call It Nothing, the podcast dedicated to the lost history of '90s roots, rap, and rock 'n' roll. I’m your host Lance Davis and today we’re going back to 1994.

But, before we dive in I wanna give shout-outs to four people who recently joined the Don’t Call It Nothing squad, all at the $5 a month Good Beeble Level. Let’s have a round of applause for Lex Ames, RJ Simensen, Rick Crelia, and Scott Clark. “What?!?! Are you kidding? We got us a family here!” Gentlemen, you are now officially deputized to spread the Don’t Call It Nothing gospel. If you dear listener wanna support DIY musicology at the $5 / $20 / $50 a month level — that’s right, go nuts — go to dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com and click on the Buy Me a Coffee! button right at the top of the page.

OK friends, we need to talk about the blues. More specifically, why did Gen X largely abandon the blues? This is the American root music. The life source. The rock ‘n’ roll genome begins here. Lemme just check my notes. Oh right, white people ruined it [laughs]. Hey, at first it wasn’t so bad. White people learned to appreciate the blues and a few of them started playing it. A few intrepid whites even credibly mastered the form. Unfortunately, the generation that came of age in the 1960s didn’t just appreciate the blues, they held it fucking hostage and repeatedly assaulted it until all that was left were guitar heroes O facing their way through 17-minute solos and an audience of middle class hippies and faux revolutionary hipsters engaging in what Ulrich Adelt perceptively called a “romantic embrace of a poverty of choice.”

Mmm … hold on. Can we savor "romantic embrace of a poverty of choice" for just a good bit. That’s good criticism. I got that from Adelt’s 2007 PhD dissertation, Black, White and Blue: Racial Politics of Blues Music in the 1960s, which later became the book, Blues Music in the Sixties: A Story in Black and White. A few pages after his glorious turn of phrase, Ulrich unloads his clip and catches a few white bodies with the following passage. Now, this is dry academic writing, so afterwards I’ll translate. Adelt writes:

An analysis of the ways in which white male power is deployed by seemingly counterhegemonic movements like those associated with the 1960s has lost nothing of its urgency. Therefore, with my dissertation I hope to contribute to scholarship on the history of racial formations in the 1960s as much as I hope to contribute to scholarship on blues music. Interestingly, in my particular case, white male power was mostly expressed through the appropriation of black masculinity. This explains my strong emphasis on male performers, cultural brokers, and fans. Women are notoriously absent from blues discourses of the 1960s.

--Ulrich Adelt, Black, White and Blue: Racial Politics of Blues Music in the 1960s, p. 9

Let’s translate, ok?

White male power = New boss unironically says shit like “the man” and “my revolutionary brothers” like he’s not the old boss

Seemingly counterhegemonic movements = Racist, but wants credit for being anti-racist

Has lost nothing of its urgency = We’re not studying this because white boomer liberals refuse to see themselves as part of the problem. That’s fun.

Appropriation of black masculinity = See: Mick Jagger. Also see: blackface.

Male performers, cultural brokers, and fans = Gatekeepers

Women are notoriously absent from blues discourses of the 1960s = Sexist, but wants credit for being anti-sexist

Why do you think the movie Get Out works? The villains in the movie aren’t maga rednecks. No, the white people in the movie make it very clear they’re good liberals. They would’ve voted for Obama a third time if they could’ve. Darn rules! [grrrr] That they wear black people like a suit isn’t an issue because they’ve already convinced themselves they’re the good guys. White men want to control black bodies, black culture, and black consciousness – shout out Lawrence Levine – and then demand the right to be seen as heroes instead of villains. We all know this is how white supremacy works, right?

That Brits became as obsessed with the blues as white Americans makes perfect historical sense. Both societies spent centuries explicitly defining themselves in opposition to brown “primitives” who were archetypes more than people, forget about being equals. Thus, the blues became just another resource to extract, no better or worse than oil, gas, coal, gold, platinum, diamonds, copper, ivory, timber, sugar cane, coffee, cocoa, rubber, coconuts, pineapple, bananas, and of course, king cotton.

Let us return to Ulrich Adelt because he specifically addresses this. He writes:

“I argue that attempts by young white audiences to reject white middle-class culture, racism, colonialism and fascism oftentimes took form in a nostalgic recreation of a safe blackness that predated the Civil Rights Movement. Listening to and playing the blues, then, was constructed as an anti-racist move, but instead of challenging racial classifications or even grappling with contemporary black politics, white performers, audiences and cultural brokers created a depoliticized and commercially charged blues culture.”

Nowhere is this black appropriation more comically apparent than in the recordings of John Sinclair, poet, self-styled ‘60s radical, White Panther, and briefly a mentor to the MC5. He’s the perfect avatar for “the white negro,” Norman Mailer’s postwar caricature of blackness that was basically a permission slip for white people to act a fool. To wit.

[laughing] What am I hearing??? I didn’t realize John Sinclair was Ned Flanders’ dad.

This isn’t about individual racists or determining who can authentically play the blues. No no, that ship has sailed. This is about honestly reckoning with a couple different elements of the ‘60s counterculture that don’t match the advertising, shall we say. One is their consistent exotic othering of minorities and the other is the wholesale displacement of black people from the genre that they created. Nowhere is this more sickeningly evident in the coverage of Jimi Hendrix. White journalists at the time, especially the Brits, played up his “Wild Man from Borneo” schtick, the big, bad Negro coming for your white women. And of course Jimi obliged them by humping his amps, burning his guitar, and playing into all of those black stereotypes that fascinated whites for centuries.

After Monterey Pop, Americans followed suit, but we had our own cultural reference points: Jim Crow, minstrelsy, blackface, etc. And as ridiculous as it sounds in 2021, the counterculture had serious conversations about whether Hendrix “played black enough.” It’s not that the hippies didn’t love Hendrix. Of course they did. Everyone did. It’s that this love was filtered through a deeply troubling racial lens that played up his otherness. For example, a month after Jimi died in September 1970, Rolling Stone ran an essay seemingly celebrating the late guitarist.

In the third paragraph of his essay unironically titled, Jimi Hendrix: An Appreciation, author John Burks writes the following:

“The sexual savage electric dandy rock and roll n-word hard-R hey who’s that over there it’s Patti Smith looking uncomfortable capital P Presence exclamation point.” You know why this is so reprehensible? Because Burks wasn’t some rogue writer hacking the system from within to take down the counterculture [laughs]. This was rote. This was banal. Everyone at Rolling Stone saw n-word hard-R and signed off on it. [white guy voice] “Looks great, JB. Thought you might’ve went a little far with electric dandy. I mean, Jimi’s no homo amirite???” And let’s be real. Millions of white readers rolled right over that passage without blinking.

The unremarkableness of Rolling Stone’s racism was as unremarkable as John Sinclair’s blackmouth patois. None of this is defensible, but that won’t stop white boomer men from trying [laughs]. Remember what Ulrich Adelt wrote back in 2007. “An analysis of the ways in which white male power is deployed by seemingly counterhegemonic movements like those associated with the 1960s has lost nothing of its urgency.” This is as important in 2021 as it was in 2007 as it was in 1994. Oh shit, I was supposed to talk about ’94, wasn’t I???

That was Jack O’Fire, an Austin, Texas punk blues force of nature featuring the legendary Tim Kerr of Big Boys and Poison 13 on guitar and Walter Daniels on harp. That was a cover of “Hate To See Ya Go” by Little Walter and His Jukes, originally recorded and released in the summer of 1955. Now, this is kind of a cheat because Jack O’Fire originally released this song in 1993. However, it was subsequently released on the 1994 Estrus compilation, The Destruction Of Squaresville, which is how I got turned onto it.

I was lucky enough to see Jack O’Fire on back-to-back days. On May 27, 1994, they played Crock Shock at the Crocodile Cafe (hence the name) with The Woggles and Man Or Astroman? Amazing show. Crock Shock was a spinoff of Garage Shock, the badass garage punk festival created by Estrus and held in their native Bellingham, straight up I-5, an hour and a half north of Seattle. The next day, Jack O’Fire played an in-store at Fallout Records and I was right up front with my roommate at the time, Greg Collinsworth (American Junk, Muzzle, The Band That Made Milwaukee Famous, Small Change).

Kerr was in constant motion, all spinning dreadlocks, big smile, and slashing guitars, but the real revelation was Daniels. He stalked the floor — as he did the stage the previous night — attacking his harp like he attacked his gravelly vocals. The rhythm section was Dean Gunderson from Seattle’s Cat Butt on upright bass and Josh LaRue holding the cacophony together by the skin of his traps. I hadn’t heard the Fat Possum dudes yet, so I didn’t know there was some righteous blues drone taking place in north Mississippi. I also didn’t know yet about Lester Butler and The Red Devils. So, 1994 me was stoked that these punks were making the blues sound fresh and exciting again.

I got turned onto JOF by my Chico homeboy, Sean McGowan, who was living in Austin and fronting a punk band called The Chumps. He raved up and down about Jack O’Fire and mentioned that one of his photos appeared on the cover of Squaresville. He was right on both counts. The picture of Walter Daniels playing harmonica was indeed on the cover and on stage those Austin motherscratchers came for scalps. It wasn’t just that they were breathing life into the blues canon (like The Red Devils), it’s that they were transforming every song into the blues. So, you’d get a Howlin’ Wolf, you’d get a Little Walter like we heard, you’d even get a Chuck Berry, all of which were supposed to sound bluesy. But, Jack O’Fire brought legit blues centrifugal force to songs by The Sonics, Small Faces, Lyres, and Joy Division.

That’s Austin’s Jack O’Fire with "No Love Lost," a can o’ whupass from noted blues band, Joy Division. And with that let’s return to the idea of Gen X and the blues. What’s more likely? That Gen X didn’t like the blues because we had no soul and couldn’t figure out why these singers kept repeating the first line of each verse OOORRRRR were we turned off by years of mediocre white blues bands turning the genre into self-parody? The irony is boomers were right to be enchanted by the blues. It’s such a sturdy form that you can rearrange an Ian Curtis song so that it makes perfect sense as a rockin blues.

Like country, bluegrass, and the blues, the problem was never the root genres themselves. The problem were self-appointed gatekeepers who decided what was — and who was — authentically country, bluegrass, and blues. This is why I’m stanning so hard for bands like Bikini Kill, Uncle Tupelo, and now Jack O'Fire. These bands weren’t interested in creating punk, country rock or blues holograms. Jack O'Fire was returning the blues to the juke joint and not in a performative way, like a major label blues band recording an acoustic blues album at union scale. Jack O'Fire was recording it DIY style because that’s all they could afford [laughs]. But, this is a good thing and should be valued. Just as importantly, they injected some fresh blood into the genre. [mock horror] “Oh no, they covered Joy Division. What’s next, a Small Faces cover that evokes Freddie King and Booker T & The MGs? That’s not canon!”

That’s Jack O’Fire with “Own-Up Time,” a Ronnie Lane/Steve Marriott instrumental from the Small Faces’ debut LP. Daniels is again the revelation. Revelator? His harp is powerful and overdriven like a second electric guitar, toying with feedback as Kerr mostly opts for slashing, horn-like phrasing and Pepper Wilson’s organ carries the melody. However, from 1:01-1:20, Kerr and Daniels are like Hearns and Hagler throwing bolos in a dazzling eight-bar exchange that’s definitely a highlight of Squaresville.

So, before I leave you to track down The Destruction Of Squaresville and these various Jack O’Fire singles, what did we learn today? First of all, the blues rules. The boomers were right to crush hard. Where they were wrong was objectifying black musicians like they were in a zoo guffawing at the sexual savage electric dandy rock and roll n-word hard R exhibit. All this romantic nonsense about the oversexed lone wolf Negro blues musician is (and was) profoundly racist colonial bullshit.

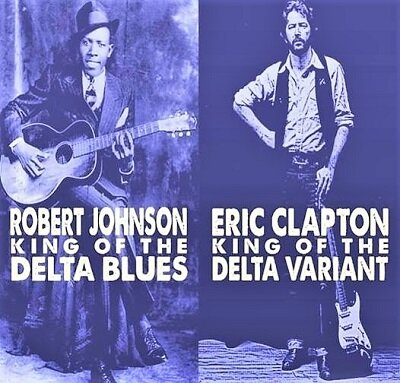

Black blues musicians were just people working on their craft in the immense shadow of white supremacy. In fact, the entire myth of Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil is pure, unadulterated caucasity. [sarcastic white guy] “A black man couldn’t possibly get better by honing his chops. I mean, that’s what white musicians like Eric Clapton do. Black people can only achieve Godhead by invoking Negro voodoo. Everyone knows that.”

Pffft.

There’s a passage in the liner notes of Jack O’Fire’s 1993 EP, Six Super Shock Soul Songs. It’s attributed to Big Daddy Soul, who I’ve always assumed was either Kerr or Daniels, but I guess it could be a third party. Anyway, it reads:

"Jack O'Fire is not pretending to be black or taking advantage of a situation. If we were, we wouldn't be listing the authors of the lessons we present. We hope that someone who is struck by a particular lesson will go straight to the source and study what the original author has to teach. We also hope that YOUR intelligence reveals that Emotion & Spirit Expression (music being a product) has nothing to do with one's particular color!"

--Big Daddy Soul (pseudonym of either Kerr or Daniels) in the Six Super Shock Soul Songs liner notes, 1993

You don’t write that unless what I’ve said here today is true. These guys understood they existed in a context in which the genre was devalued by years and years of blues tourists. Big Daddy Soul is saying what I’m saying. If you love the blues, treat it with respect. It’s not about making white lawyers comfortable with their appropriation. It’s about acknowledging that this primordial American music was enriched by the best white blues musicians simultaneously as it was colonized by white people displacing the root black audience. It’s ok to interrogate this part of the genre’s evolution.

With that in mind, let’s finish off today’s celebration of the blues with Jack O'Fire’s acoustic run through Willie Dixon’s "Seventh Son." Kerr and Daniels weren’t trying to be black or pandering to the blues festival crowd. They were just dope-ass musicians trying to give something back to the genre that gave them so much. Walter Daniels' harp playing is righteous fury throughout and Tim Kerr shows off his slide guitar prowess. It’s simple, stark, and beautiful. Just like the blues.

You don’t have to be a seventh son of a seventh son to subscribe to this podcast, but that’s what Muddy Waters would’ve wanted. No pressure. Please go visit the Don’t Call It Nothing Facebook page and website. Dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com. Like, comment, become a member, tell yo mama, and tell a friend.

Talk to ya next time when we launch into space with The Flaming Lips in 1995!

From Four Until Slate

Uncle Tupelo w/Freedy Johnston, Houston, TX, March 6, 1993. Also, a good bridge to next week's podcast.

Houston, TX, March 6, 1993.

Also, a good bridge to next week's podcast.

Podcast Episode 6 - 1993 (Anodyne)

The idea that Nirvana dethroned Michael Jackson obscures the fact that Garth Brooks and mainstream country dethroned both of them. “Black Or White” wasn’t the enemy. The “American Redneck Bar Association,” that was the enemy. Red hat, gun rack, fragile ass, antivax, flag-haggin, honkkky ass tonkers. I spoke last week about the conservative counter-revolution of the 1990s. Who the hell do you think they were listening to? That’s right. Hat heads like Garth Brooks. So, if you’re looking for actual signs of musical counter-COUNTER-revolution in the 1990s, than you need to go looking, not for grunge, but for country music refusing to play by boring as fuck Nashville rules. In other words, we need to talk about Uncle Tupelo.

Transcription

Theme Song: Mike Nicolai, “Trying To Get It Right” [Bandcamp]

Welcome to Don't Call It Nothing, the podcast dedicated to the lost history of '90s roots, rap, and rock 'n' roll. I’m your host Lance Davis and today we’re going back to 1993.

Before we dive in I wanna give a quick shout-out to Pete Sufka, who joined the Don’t Call It Nothing family this week at the $5 a month Good Beeble Level. Thank you Pete. If you dear listener wanna support DIY musicology at the $5 / $20 / $50 a month level go to dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com and click on the Buy Me a Coffee! button right at the top of the page. Cool? Cool.

Now, I’ve spent a fair bit of time on here challenging boomer myths about classic rock, but turnabout is fair play, my friends. To act like Gen X also doesn’t have its debunkable lore would be silly at best, hypocritical at worst. This is true for even the leading edge of Gen X, which I’m gonna assume includes everyone listening to this podcast or should be listening to this podcast. For example, anyone who was even remotely paying attention to indie rock/college rock in the early ‘90s knows that Nevermind bumped Michael Jackson’s Dangerous from the top of the album charts. That happened on January 11, 1992, and “dethroned the King of Pop” was the phrase du jour. In fact, three weeks later Nevermind also bumped Garth Brooks’ Ropin’ The Wind off the charts. The King of the Hat Acts. Obviously, the symbolism was immense. Grunge defeated mainstream pop and mainstream country. We won. In your face, normies!

Only that’s not what happened. We didn’t win. And knowing how this all played out, you can argue that though Nirvana won, I’m not sure Kurt Cobain won. He most definitely outkicked his coverage and found himself in the unlikeliest of positions: the misfit prom king. But, was that a net positive? Magic 8-Ball says, “Outlook not so good.”

Let’s look at this from the 30,000 foot (view). That’s where the real story is. I’m gonna give you some stats and don’t worry about keeping track. I’ll sum up at the end. I just wanna give you the context. OK, on September 28, 1991, just a few days after Nevermind was released, Garth’s Ropin’ The Wind ascended to #1 on the album charts. Not the country charts. The pop charts. It was knocked off by Use Your Illusion II for a couple weeks, but went back to #1 on October 19 and stayed there for seven weeks. Then it’s Achtung Baby for a week, Dangerous for four, Nevermind for one, Ropin’ again for two, back to Nevermind for one, and then back again to Ropin’ for EIGHT weeks. When its run at the top was over Ropin’ The Wind had spent 18 of the previous 27 weeks at #1.

Garth then released The Chase and THAT album spent eight weeks at #1 in late 1992. In August ‘93, Brooks then released In Pieces and that spent five weeks at #1. When all was said and done, from late September 1991 to late October 1993 – just over two years – a Garth Brooks album held down the top spot on the pop album charts for 31 out of 100ish total weeks.

Please note, too, that smack dab in the middle of Garthapalooza, Billy Ray Cyrus introduced line dancing and “Achy Break Pelvis” into the American mainstream and white people were never the same. Even The Bodyguard soundtrack, the other massive record released in this period, was fueled by a Dolly Parton song. My friends, “we” didn’t win shit. Garth Brooks won. Mainstream country won. The normies won. To be fair, Dolly also won and she deserves all the love because she invested part of her earnings from Whitney’s cover (of “I Will Always Love You”) in a black section of Nashville. True story. Look it up.

Everything Cuts Against the Tide

Is it possible that we misinterpreted the significance of Nirvana’s mainstream breakthrough because it’s what we wanted to believe? I think so and there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. The need to feel like you have value is hardwired in us, so when a band you like inexplicably crashes the pop culture party it feels like vindication.

The thing is … the idea that Nirvana dethroned Michael Jackson obscures the fact that Garth Brooks and mainstream country dethroned both of them. “Black Or White” wasn’t the enemy. The “American Redneck Bar Association,” that was the enemy. Red hat, gun rack, fragile ass, antivax, flag-haggin, honkkky ass tonkers. I spoke last week about the conservative counter-revolution of the 1990s. Who the hell do you think they were listening to? That’s right. Hat heads like Garth Brooks. So, if you’re looking for actual signs of musical counter-COUNTER-revolution in the 1990s, than you need to go looking, not for grunge, but for country music refusing to play by boring as fuck Nashville rules. In other words, we need to talk about Uncle Tupelo.

That was Uncle Tupelo from November 11, 1993, at Slim’s in San Francisco with “Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down,” a song about the music industry. Just kidding. Everyone knows it’s about white supremacy. That was recorded by hero of the Tupelo extended family, Shayne Stacy, you should check out his YouTube channel, 3.Cameras.and.a.Microphone. Quality live stuff, lots of Tupelo, and this audio might be his best. Max Johnston kills it on fiddle and Ken Coomer’s dropping a mean train beat, Jeff Tweedy’s vocal has the ideal rasp:scream ratio, and when Jay Farrar comes in with the low harmony at “I heard the voice of Jesus say” … perfection.

This performance actually took place about a month after Anodyne came out. In fact, you’ll enjoy this, the album was released on October 5, 1993. The #1 album at the time? Garth Brooks’ In Pieces, which was displaced at #1 the following week by none other than In Utero. Yay us! Oh wait. In Pieces went back to #1 the week after. Which means that a Nirvana album twice knocked Garth off the top of the album perch only for Brooks to reclaim the top spot the following week. Nirvana basically had a halftime lead. Nothing wrong with that. I’d rather have a halftime lead than not have it, but you know. It’s symbolic.

But symbols can have real value. Which brings us back to Uncle Tupelo. There was so much written at the time – including by me, so I’m part of the problem, I’m complicit – that the band was extending the country rock tradition of everyone from Neil Young and Creedence to Buck Owens and Jason And The Scorchers. That much was readily acknowledged by all parties. But, how you FELT about the band, I think that broke along generational lines. For Gen Xers like myself, who were getting into country rock for the first time in our early 20s, UT was OUR band. We loved the precursors, of course, but that Uncle Tupelo was more or less our age mattered because their concerns felt like our concerns. I’m guessing members of Slobberbone, Drive-By Truckers, Grand Champeen, Two Cow Garage, and Glossary would agree. And as easy as it is for me to make fun of boomers for their rock star fetishes – the various cults of Lennon, Jagger, Richards, Dylan, Springsteen, etc. – those songwriters were writing for them. Those are their guys. The problem is that their guys are allowed to be “cultural icons” and our guys are marginalized and minimized.

This generational difference is perfectly illustrated by the editors of No Depression, the alt.country magazine that started publishing quarterly in 1995, graduated to bimonthly soon after, and went on a surprising 13-year run as a published entity. Still a presence online, too, so you have to consider the enterprise an American success story. Peter Blackstock, one of the editors, was born in ’66, which makes him an OG Gen Xer, but also someone who might be vulnerable to echoboomeritis. Grant Alden, the other editor, was born in ’62, which puts him solidly in the late boomer camp. You wouldn’t think four years would be that significant, but I think it is and anecdotally, this schism matches my experience. In 2007, Blackstock and Alden were part of a feature that ran in the Seattle Weekly called “Jukebox Jury.” It’s still online, I’ll link to it in the transcription. They had this exchange about Uncle Tupelo’s version of “No Depression.”

Blackstock: We have to reference this song all the time. We have to explain that our (magazine) name comes from this Uncle Tupelo song from an album of the same name that [Uncle Tupelo] learned from Mike Seeger and the New Lost City Ramblers, who were covering this old Carter Family song from the 1930s, which sort of traces the history of where this song is coming from originally and how it got revived in recent years.

Alden: I think we had been publishing about two years before I actually owned any Uncle Tupelo records, though I can remember when Anodyne [1993] came into The Rocket office. I had heard about them and I was predisposed to like them. I played it at high volume and annoyed the office and then gave it to a writer who adored them. I thought, “Well, they’re not very good.”

[heavy sigh] WHAT???

That’s Uncle Tupelo from September 5, 1993, at the Music Café in Copenhagen, Denmark, with the old Carter Family song and title track from their 1990 debut. Look, Alden isn’t required to like anybody. But, don’t you find that quote strange and weirdly dismissive? If two men started a metal magazine and one of them said he’d been publishing two years before he owned a Metallica record and mehhh, you wouldn’t find that off-putting? This wasn’t the best publication for alt.country. This was the ONLY publication for alt.country. Option had a cover story on the genre in 1993 featuring Uncle Tupelo and Maria McKee, but that was a one-off. No Depression was it. And even in a random interview 13 years after their final show, Uncle Tupelo still can’t get full credit. It can’t be, “This Uncle Tupelo cover was so good that it made us go wanna track down the original,” which is exactly what happened. That’s what happened for everybody who heard that song. But no, just like with Kathleen Hanna and Bikini Kill last week, boomer gatekeepers can’t wait to go out of their fucking way to diminish, condescend, and gaslight the contribution of Gen Xers, “Ahh that’s cute you did a thing. But you’re not that good. Calm down.”

Do You Want New Kid In Town or Do You Want The Truth?

In fact, Uncle Tupelo was our Velvet Underground. You heard me. Creedence is the better stylistic comp, sure. But, see if this sounds familiar. The Velvets had two albums that combined rock dissonance with a sly melodic underbelly, then released a quiet folkie stopgap, then released a final album featuring accessible, if contemporaneously out of step rock ‘n’ roll. Also consider context. What made the Velvets the Velvets was that they weren’t The Beatles. They went dark because The Beatles represented light. To be fair, we all know The Beatles went dark – “Helter Skelter,” “Happiness Is A Warm Gun,” “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” – but they were dilettantes dabbling, not covering themselves head to toe in shiny shiny leather. More importantly, The Beatles were the biggest goddamn band in the world and the Velvet Underground was … well … the opposite of that.

Fast forward to 1993 and while Garth Brooks himself wasn’t Beatles big, he was fucking massive. This is a man who bragged about being influenced by Journey and KISS, so competent, calculated, show businessy country music influenced by “Don’t Stop Believin’” and Gene Simmons was deemed by the mainstream country audience to be the platonic ideal. Keep in mind that throughout the decade, parallel with Brooks’ massive run up the charts, so too did The Eagles’ Greatest Hits (1971–1975). Per Wikipedia – so, obviously true – it was certified 12× platinum in August 1990, 14× platinum in 1993, 22× platinum in 1995, and 26× platinum in 1999. Folks, that’s Thriller numbers.

So, what does this mean?

It means that we’ve fundamentally misunderstood the 1990s. It’s not that Garth Brooks wasn’t country. He was. But, he was also rock. It was baked into his arrangements and performance. The light show, the spectacle, that’s pure rock. Thus, the mainstream country audience was actually a country rock audience. The Eagles were the giveaway. If you’re doing Thriller numbers, whatever you’re playing IS the mainstream. And what The Eagles specialized in was safe, comfortable, inoffensive, country rock, not unlike Garth Brooks.

Given this milquetoast reality, root down American rock ‘n’ roll with traditional country instrumentation and an honest reckoning of the human condition was not only the opposite of Nashville’s fast food country, it was the most punk rock response possible. Farrar and Tweedy made the best rock album of 1993, the best country album of 1993, and inspired hundreds of bands to take up arms against the normalization of bland country rock — and bland country. The fact that choosing this route almost certainly guaranteed commercial failure was part of what made it punk rock. The punkest element of all, though, was Farrar’s absolute command of the country form. His version of the genre makes guys like Brooks, Henley, and Frey sound like the businessmen they always wanted to be.

That’s Uncle Tupelo, again from that fantastic Slim’s show on November 11, 1993, and that just might be the greatest Farrar vocal ever. The final track on Anodyne, “Steal The Crumbs” is a Farrar masterpiece as good as anything Dylan, Lennon, or Springsteen ever wrote and makes the Garth Brooks Vanilla Milkshake Experience sound like Chuck E Fucking Cheese. Anodyne is the record that spurred me into exploring the history of country music because it's country to the bone and accessible, yet not remotely commercial ("Clean Slate," "New Madrid," "High Water," and "Steal The Crumbs," all great examples). I love that Tweedy wrote a song with the lines, "Name me a song that everybody knows / And I betcha it belongs to Acuff-Rose," a reference to Nashville’s first country music publishing company, founded in 1942 by singer Roy Acuff and A&R man, Fred Rose (best known as Hank Williams' manager). The irony, of course, is that despite this lyrical touchstone there was 0% chance "Acuff-Rose" was ever ever EVER gonna get played on a Nashville radio station.

Of course, Anodyne is defiantly rock in Jay’s blistering Farrarmageddon lead guitar. His solos in "Chickamauga" (2:05-3:38), "The Long Cut" (1:22-1:50, 2:35-3:15) and "We've Been Had" (2:12-2:25) are wondrous jet engines filled with overtones and distortion. Let us also not forget Ken Coomer's heavy drums, which Tweedy admitted kept him focused. He told Greg Kot in Wilco: Learning How to Die:

“I’m amazed when I listen back to those records with Mike how cool the drumming actually is. He is totally self-taught and idiosyncratic, but his feel is dead-on. That’s the recording. But working out the nuts and bolts in rehearsal, his drumming could be like a shoe in a dryer. It was work sometimes to hear the kick drum because Mike wouldn’t play loud. And then Ken (Coomer) comes in and is just a powerhouse: tons of experience, tons of chops, and yet not so flashy that he can’t come down and play a country beat. As a bass player, I could finally relax. With Mike, I was playing and singing and hoping that I was playing somewhere near where the bass drum was. With Coomer there was no doubt where the bass drum was: it was right up my fucking ass.”

(FYI, throughout the podcast I refer to Kot’s book as Learning How to Live — instead of Die — because apparently the real title is too hard to remember. Sorry about that, Greg.)

Coomer wasn't the only new member of the band. John Stirratt, brother of Blue Mountain's Laurie Stirratt and Brian Henneman's replacement as Tupelo roadie/guitar tech joined on bass. Most critically, the band also enlisted the services of Max Johnston, best known at the time – if known at all – as Michelle Shocked's brother. He'd met Farrar and Tweedy on a short-lived Shocked tour with The Band and Taj Mahal when he was backing up his sister. He and the Tupelos would hang out after shows, jamming into the night on old country covers. Johnston is a supremely talented multi-instrumentalist and the album's MVP. In fact, his fiddle is the first sound you hear on Anodyne, mournfully sawing and mirroring Farrar's brooding resignation in "Slate." Max's dobro slides are the best part of "Fifteen Keys," where he plays the main riff, the melody in the chorus, and an eight-bar solo. And finally, how about that banjo hook in "New Madrid?”

Perhaps my favorite bit of Johnstonia is how his lap steel weaves with Lloyd Maines' pedal steel on the title track (“Anodyne”). Having two steels doesn't make any sense on paper, but it gives the song such a wobbly intoxication. It's like "Albuquerque" or "Tired Eyes" from Tonight's The Night, but with TWO Ben Keiths. So wonderful. The funny thing is that despite his heavyweight contributions, Max wasn't sure he was ready for Tupelo time.

"I was really nervous because I was wondering if I could even play in a rock band, but Jay and Jeff knew the music I knew and a lot of music that I should have known. I hadn't really listened to the Louvin Brothers or even Loretta Lynn and Ernest Tubb. They turned me on to all of that stuff within the first few weeks and I started getting more comfortable with the idea of playing with them."

–Max Johnston to Greg Kot, Wilco: Learning How to Die, 2004, p. 75

One of Anodyne's most charming features is the fact it was recorded live at Cedar Creek Studios in Austin. Where the March album was mostly live, it included a few overdubs. However, that album's relative spontaneity was a response to No Depression and Still Feel Gone, which were Overdub City. Anodyne was a reaction to all of the above, as well as "the growing trend in the early '90s to construct recordings piece by piece on the computer," which is what Farrar says in the liner notes to the 2003 Anodyne reissue. So much so that it contains no overdubs and a handful of mistakes. Not that the band wanted mistakes, per se, but if a few clams was the price to pay for uninhibited rawness, then so be it. No other track symbolized the band's studio vérité aesthetic quite like their duet with Doug Sahm. "Give Back The Key To My Heart" originally appeared on Sahm's 1976 LP, Texas Rock For Country Rollers, my favorite album in the Sahm catalog and a title that could've been apropos for Anodyne. This was music between genres. Music that checked multiple boxes but fit comfortably in none. In other words, it was rock 'n' roll, and few people have epitomized that free spirited musical polyglot quite like Sir Doug.

In his 2013 memoir, Falling Cars and Junkyard Dogs: Portraits from a Musical Life, Farrar says of Sahm:

"Doug's conviction and enthusiasm for music was palpable, contagious, and always audible. In 1993, while recording with Uncle Tupelo, Doug hit a microphone stand with his guitar headstock (which can be heard on the recording) while getting into the groove. But no matter – it's all about the groove anyway. That was the lesson learned."

–Jay Farrar, 2013, p. 120

The combination of new band members and live recording led to UT largely abandoning the stop-start arrangements that had made those first two records so much fun. In Kot's book about Wilco, Tweedy says of the Anodyne material, "There was more of a pop element or a buoyancy that just didn't seem to be part of Uncle Tupelo before. But, through John (Stirratt's) playing and Ken's playing and my songs at the time, it was just more tuneful and less contrived arrangement-wise." (Kot, Wilco: Learning How to Die, 2004, p. 79). I agree about the pop element, especially in a song like "No Sense In Lovin,' which clearly presages A.M. However, I strongly disagree about the idea that the old arrangements were contrived. As Tweedy himself admitted, Heidorn wasn't a heavy player like Coomer. Early Tupelo songs featured Minutemen-esque stop-start arrangements because that played to Heidorn's strengths. That's not being contrived. That's being a smart bandleader. Now, maybe by the time of Anodyne Tweedy (and the band) had evolved past that need for the stop-start. Fair enough. But, that doesn't retroactively make those early songs contrived. They were honest representations of UT 1.0 and the more stripped-down arrangements were honest representations for UT 2.0. Both great, but great for different reasons.

That’s basically the title track of this podcast and my forthcoming book, Don’t Call It Nothing: The Lost History of ‘90s Roots, Rap & Rock ‘n’ Roll. Tweedy sings,

“Don’t call it nothing

This might be all we’ll ever have”

That’s my mission statement right there. It might also be the Gen X motto [laughs]. “Nothing” is a track from their 1991 album, Still Feel Gone, one of the greatest albums ever, as is Anodyne. And I’ve gone all this way discussing Anodyne’s undervalued cultural importance and its deceptively revolutionary musical acumen, but I haven’t even bothered to mention that it’s all that AND one of the greatest breakup albums you’re ever gonna hear. Richard Byrne of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the first journalist to champion the band in print, said to Greg Kot in Wilco: Learning How to Die:

"With Uncle Tupelo, it was turning into more like The Beatles, where Paul McCartney, John Lennon, and George Harrison were bringing in their songs at the end and competing for space on the albums. It's harder to sustain a band dynamic in that situation. Especially when you have record company machinery saying, 'I like his song better,' and making it the single. To someone like Jay, who is suspicious of record label politics anyway, that's going to be the sound of fingernails on the chalkboard. Jay didn't like what he saw coming down the road and I think Jeff loved it."

–Richard Byrne to Greg Kot, Wilco: Learning How to Die, 2004, p. 87

Speaking of great for different reasons, that was Jay and Jeff in 1993. Where Farrar was employing bloody Civil War metaphors to describe his state of mind ...

"Chickamauga's where I've been

Solitude is where I'm bound"

– Chickamauga

... Tweedy was hopeful that time apart would reignite the passion, even if he suspected that he was the only one who wanted that to happen.

"Now if it's to be

And if you still believe

Come on let's take the long cut

I think that's what we need"

–The Long Cut

"If you come back for a while

You could see

Exactly what you've always meant to me

But you don't wanna know"

–No Sense In Lovin’

However, Farrar was steadfast. He didn’t wanna know. Uncle Tupelo was done.

"Can't seem to find common ground

I can see the sand and it's running out"

"No sign of reconciliation

It's a quarter past the end"

–Steal The Crumbs

Farrar was under no illusions.

“It was the kind of situation that just wasn’t going to end smoothly. The fact that Jeff and I each wrote songs separately and essentially shared a band to record them was the primary reason the band split. When we started, we agreed to share the songwriting credits in the spirit of Lennon/McCartney, Jagger/Richards, and Strummer/Jones, which initially led to a few collaborations, but ultimately led to feelings of living a lie, as we wrote nearly completely separate. The irony is that we knew The Beatles and Clash had ended in splits. I think that under the circumstances we both put forward a good effort in encouraging each other to write songs and remain in the same band for as long as we did – seven years in Uncle Tupelo and three years before that (in the Primatives).”

As much as I love Anodyne, you can make a decent argument that it's Uncle Tupelo only by contractual obligation. One of the reasons I chose a Still Feel Gone song for the title of this book – other than the fact it fits perfectly – is that it's the apex of the Farrar/Tweedy/Heidorn relationship. Heidorn may not have been an according to Hoyle great drummer, but he was the glue that kept the band together for as long as it did and when he left the infrastructure slowly disintegrated. But, instead of lamenting the band's demise, I choose to celebrate the fact that Uncle Tupelo gave us one final, magical album before leaving the building for good.

Purchase Anodyne [Discogs]

You don’t have to fight fire with unlit matches to subscribe to this podcast, but you know you wanna. Please go visit the Don’t Call It Nothing Facebook page and website. Dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com. Like, comment, become a member, tell yo mama, and tell a friend.

Talk to ya next time when we visit 1994!

Everything Cuts Against the Tide

This should be fun. Friday's podcast is tackling this band, this album, and this moment.

This should be fun. Friday's podcast is tackling this band, this album, and this moment.

Podcast Episode 5 - 1992 (The Punk Singer)

"I just think there's a certain assumption that when a man tells the truth, it's the truth. And when, as a woman, I go to tell the truth I feel like I have to negotiate the way I'll be perceived. Like there's always suspicion around a woman's truth. The idea that you're exaggerating. There's this whole fear that I'm gonna have finally fucking stepped to the plate and told the truth and someone's gonna say, 'Ehhhh, I don't think so.'"

--Kathleen Hanna

Transcription

Theme Song: Mike Nicolai, “Trying To Get It Right” [Bandcamp]

Welcome to Don't Call It Nothing, the podcast dedicated to the lost history of '90s roots, rap, and rock 'n' roll. I’m your host Lance Davis and today we’re going back to 1992. But first, I wanna give shout outs to two people who just joined the Don’t Call It Nothing family. Mike Nolen, proud Oregon Duck, Gourds enthusiast, and Richmond Fontaine completist. I see you, good sir. Also, much love to Mike Manson who is definitely not regretting his move from San Francisco to Austin. You know those cool evenings, brisk walks in North Beach? Pffft. Who needs that stuff when you have the surface of the sun at your disposal? No seriously. Thank you gentlemen. You are seen. If you dear listener wanna support DIY musicology at the $5 / $20 / $50 a month level go to dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com or just go to buymeacoffee.com/pantsfucious and sign up.

OK, so last week I finally saw The Punk Singer, Sini Anderson's 2013 documentary about Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill, Le Tigre, and The Julie Ruin. Actually, that’s not quite accurate. I saw it for the first time last week, saw it for the second time a day later because I had the 48 hour rental from Amazon. So, why not? And then I couldn’t stop thinking about it, so I watched it again earlier yesterday morning. Good God, Lemon. What a movie, what a life. I’m so impressed by Kathleen’s evolution and her, all things considered, normality. She’s totally relatable, she’s funny, sympathetic, empathetic, and a couple moments really, really resonated with me, that echo in spirit some of the things I’ve been saying here on the podcast.

The first is a quote from Tammy Rae Carland, who is currently provost of California College of the Arts up in the Bay Area, but in the late ‘80s was a student at Evergreen State College in Olympia with Kathleen. So, they were friends who started an art museum together called Reko Muse, started a band together called Amy Carter, and Carla later did artwork for Bikini Kill. Very politically motivated, very feminist, which is where the first quote comes into play. Tammy Rae says:

"A very clear memory I have of Kathleen is her showing me a copy of a copy of an article from Time Magazine. 'Is Feminism Dead?' We both got really emotional. It couldn't be dead because we were living it. We were doing it, thinking it, and feeling it. How could it be dead?"

—Tammy Rae Carland in The Punk Singer, 2013

That issue was published on June 29, 1998, and featured, from left to right on the cover, Susan B. Anthony, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Ally McBeal. NOT Calista Flockhart, the actress who played Ally McBeal. No, the Time cover specifically says Ally McBeal. I’m sure as Flockhart waded through the hate mail and angry emails from long since discarded AOL accounts blaming her for killing feminism, she just chuckled to herself. “Oh you guys. This is a total misunderstanding. You’re gonna laugh when I tell you that I’m not actually the person on the Time cover.”

Anyway, think about the Time cover from Hanna’s perspective. She spent nearly a decade touring her ass off, fighting the good fight in dingy bars and clubs, youth centers, ballrooms, college campuses, and in front of the goddamn US Capitol, spreading the gospel to and for women and girls when there was no cultural incentive to do so. The band’s notoriety throughout the decade certainly helped spike their fanbase. But, there was a dark side to that notoriety in that Kathleen’s outspokenness invited vicious attacks by mediocre dudes feeling threatened — and sometimes Courtney Love. But, men would intimidate, harass, talk shit, try and take upskirt pics near the stage, and do you think she had Metallica’s security crew to help her out??? Ok, she was tough and yes, there was safety in numbers to a degree. The Punk Singer makes it clear there was a collective mentality. But, these were still combustible, potentially dangerous environments, especially for a woman, and that kind of constant hostility is eventually gonna break you down emotionally and physically. So, to have Time basically say, “Oh that’s cute you were in a band. But, the adults in the room are talking about real feminism,” with a little pad on the head. It’s a fucking kick to the crotch, right?

So, that leads me to the other quote. It’s near the end of the movie when Kathleen says:

“I just think there’s a certain assumption that when a man tells the truth, it’s the truth. And when, as a woman, I go to tell the truth I feel like I have to negotiate the way I’ll be perceived. Like there’s always suspicion around a woman’s truth. The idea that you’re exaggerating. There’s this whole fear that I’m gonna finally have fucking stepped to the plate and told the truth and someone’s gonna say, ‘Ehhhh, I don’t think so.’”

Kathleen is absolutely talking about patriarchy, but both of these quotes illustrate a separate but equal glass ceiling that everyone in the ‘90s ran up against. No matter how fucking hard you were working to figure out who you were and expressing yourself artistically, it was never enough. Gloria Steinem? Now she did it right. That’s how you act like a rebel girl. I’m afraid Kathleen’s “stripper antics” aren’t gonna cut it. Gen X might be the first generation to be criticized for not rebelling correctly. “Oh, you think that’s non-conformity? That’s nothing. Abbie Hoffman once shit his pants to protest the Vietnam War. Sure, he was in a Howard Johnson’s, but it was the symbolism that mattered.”

Riot grrrl was as anti-establishment as anything in the ‘60s rock malescape, but Bikini Kill’s limited musicality was weaponized against the band, as if Hanna’s deeply personal lyrics couldn’t possibly be taken seriously if they didn’t even take their music seriously. Nevermind our previous conversation that when dudes talk up the Stooges their “limited musicality” is a virtue. “Dude, ‘1969’ is only two chords, brah. Punk rock!” But, when women are involved, oh no that’s a bridge too far. Tobi Vail evolved into a seriously bitchin drummer by the time Reject All American was released in 1996, but Bikini Kill improving and evolving isn’t an interesting story. What is an interesting story? Glad you asked.

A week or so ago I wrote about HBO’s upcoming Woodstock ’99 documentary. Correction. SIX PART documentary. HBO wants it both ways. They want to critique shitty whiteboy rap rock culture while giving it a multi-part platform. I like that The Punk Singer comments on the festival. It addresses Woodstock ‘99 and moves on. Why? Because watching The Punk Singer is an implicit criticism of the festival. It’s an implicit criticism of shithead whiteboy rap rock. And it’s obviously an implicit and explicit criticism of idiot dude culture/patriarchy. Why do we need to give this nothing burger six fucking parts??? I’m sure Sini Anderson would’ve loved the marketing budget of HBO’s dumb documentary. YOU’RE RANTING, I’M NOT RANTING!

[sighs]

HBO gives it six parts for the same reason Bikini Kill became a media fetish totem for a spell in the early ‘90s. Trauma Porn. It’s a curious mutation of objectification because press coverage can code sympathetic. But, like an uncle who stares a little too long at somewhere he shouldn’t, the members of Bikini Kill started feeling like journalists were at best exploiting their past trauma for circulation numbers — what we now call clickbait — and at worst getting off on their stories of sexual assault. Hence, their semi-famous media blackout. And what’s the common denominator in the blackout and my discussion points? These women weren’t being taken seriously. As polemicists, as survivors, as victims, maybe. But, as musicians and artists they were and still are in many respects virtually invisible. What did Tammy Rae Carland say when she saw that odious Time cover? "We were doing it, thinking it, and feeling it. How could it be dead?"

That was Bikini Kill live at the Sanctuary Theatre in Washington DC on April 4, 1992. That is not on an album, but go to Bandcamp and the entire Bikini Kill discography is on there. The Julie Ruin, Kathleen’s band after Le Tigre, is also on Bandcamp. Le Tigre itself is not, but I’m pretty sure those albums are still pretty available. I guess what I’m saying is Kathleen Hanna is a national goddamn treasure! She’s the electro-punk Dolly Parton, not some “colorful footnote.” Can we get some respect for this woman???

That was Huggy Bear, Bikini Kill's British allies in gender politics and punk rock righteousness with "February 14th." That’s the final track on the Bikini Kill/Huggy Bear split LP that was released on Kill Rock Stars in ‘92. The Bikini Kill side was Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah and as I said before you can find that on Bandcamp. The Huggy Bear side was called Our Troubled Youth and good luck finding that these days. In fact, the entire Huggy Bear catalog is sadly out of print and will cost you a decent chunk of change on the used market. This is too bad because their songs, as you just heard, are also primally intense and a little advanced musically compared to early Bikini Kill.

Back in 2015, a writer from Alabama named Matt Kessler wrote a fantastic essay that ran in Pitchfork, “Searching for Huggy Bear: Riot Grrrl and Queerness in the American South.” I’ll link to it in my transcript, but here’s an excerpt that I think puts the band’s value into a proper sociopolitical context. He writes about discovering the band in 1995 from a mixtape given to him by his friend Aaron. You don’t get much more ‘90s than that. Suck on that boomers. [nerd voice] “Hey guys, let’s smoke grass and listen to my Mamas and Papas soundtrack. In stereo.” Lame. Kessler writes:

I’d heard about riot grrrl that summer on MTV. Courtney Love had socked riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna in the face at Lollapalooza. That’s how MTV’s Kurt Loder described her – "Riot Grrrl" Kathleen Hanna. MTV treated riot grrrl like a cutesy coven of witches: dangerous, but too frivolous to be taken seriously.

Riot grrrl, I was told, happened in Seattle, Portland, Olympia, Washington, D.C., and Minneapolis. According to the older boys at my high school it was a bunch of girls "singing about their periods", and Birmingham (Alabama) punks were "too smart for that." Supposedly, a couple of riot grrrls had tied a boy to a tree and "sucked his dick till he started bleeding." This was the lore.

Aaron’s mix tape was my first exposure to riot grrrl, my initiation. I was so curious about what girl rage sounded like but MTV only showcased major label bands, and the Internet was not yet a proper place for music. Anything underground required an enlightened elder passing you a tape, a zine, or a flier.

The band at the end of Side A and the beginning of Side B sounded different than the other riot grrrl bands on the tape. The singers had English accents. The songs were more militant, violent even. Being gay had never sounded so punk, and being punk had never sounded so tough. Who was this mysterious English riot grrl band of witches and fagboys?

--Matt Kessler, “Searching for Huggy Bear: Riot Grrrl and Queerness in the American South,” Pitchfork, September 28, 2015

Btw, did you notice the obsession with blood from the older boys at Kessler’s high school? Riot grrrl was songs about periods and riot grrrls supposedly punish boys by sucking their dicks until they … bleed? What??? Is it any surprise we have dumbasses now talking about Jewish space lasers? Here’s an idea. Shut yer mouth.

That was The Mummies with “Shut Yer Mouth,” a track from their only LP, Never Been Caught. They called it "budget rock." How awesome is that? Stripped down, two (maybe three) chord rock 'n' roll with Larry Winther spitting out brief, gnarly guitar solos, Russell Quan's drums spilling into the mix, and Trent Ruane's vocals in the red. This is a band who actually dressed up as mummies on stage and so loathed the concept of clean audio production that they refused to release their records on CD until the early 21st century. Classic, I love these guys. Needless to say, this album is not on Spotify and if you wanna buy a copy of Never Been Caught it’s gonna set you back a few bills. The album is about half originals (“Shut Yer Mouth” is one) and half covers. Of the covers my favorites are "Shot Down" by The Sonics, a massive influence on the band, "Justine" by Don And Dewey, and this bad mamma jamma, "Sooprize Package For Mr. Mineo," a cover of Supercharger, fellow contemporaries of the primitive.

That’s The Mummies covering San Francisco’s Supercharger, another band whose catalog is way out of print and costly. I wanted to play them because they put the lie to the idea that White Stripes brought rock back to the garage in the late ‘90s. Nah. Badass garage rockers existed all along, the gatekeepers just weren’t paying attention.

You don’t have to be a riot grrrl to subscribe to this podcast, but it might help. Please go visit the Don’t Call It Nothing Facebook page and website. Dontcallitnothing.squarespace.com. Like, comment, become a member, tell yo mama, and tell a friend.

Talk to ya next time when we revisit 1993!

I'll Keep Breathing, I Keep Breathing

It's easy to overlook or ignore how good The Gits were as an actual, working band. Maybe people feel like if you're not focusing on Mia Zapata’s death it's disrespectful to her memory, but I feel the opposite is true. Mia ended up a victim, she didn't live as a victim. She was a kickass singer, songwriter, and performer and that needs to be remembered and celebrated, too. The loss of this band is a secondary tragedy, but a tragedy nonetheless.

"Do you ever think that when you're dealing with the worst

The outcome is the best thing for you?

And by the good of evil is in the knowledge that you face it

One day you're gonna fucking have to"

–Mia Zapata, "Absynthe"

In 1992, The Gits released Frenching The Bully, the only album released during lead singer/songwriter Mia Zapata's lifetime. It’s deceptively ambitious and not all of it works, but the best songs have melodic hooks and guitar breaks that are well beyond 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 punk rock. "Absynthe" sounds like Bad Religion, but with a cool instrumental breakdown where guitarist Andy Kessler (aka Joe Spleen), bassist Matt Dresdner, and drummer Steve Moriarty each drop out and then come back in one at a time. "Another Shot Of Whiskey" is dare I say Cobainish? It should've been a single. "Second Skin" starts out like Social Distortion and ends up as one of The Gits' greatest songs. This version was actually released as a single the previous year, so for my playlists I'm including it with '91. "Wingo Lamo" was written mostly by Kessler, and lyrics are Zapata's, but Moriarty owns the song. Dude plays all the fills. "Slaughter Of Bruce" and "Kings And Queens" are particular highlights because they sound like templates for A Giant Dog, easily my favorite band of the 2010s. Intentional or not, AGD lead singer Sabrina Ellis has a lot of Mia Zapata in her. It's great to see the lineage continue.

“Mia ended up a victim, she didn’t live as a victim. She was a kickass singer, songwriter, and performer and that needs to be remembered and celebrated, too. The loss of this band is a secondary tragedy, but a tragedy nonetheless.”